- Home

- Portia de Rossi

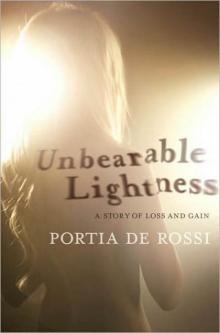

Unbearable Lightness

Unbearable Lightness Read online

Unbearable Lightness

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright © 2010 by Portia de Rossi

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Atria Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

First Atria hardcover edition November 2010

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Photograph credits: pp. 265 and 267 © Davis Factor/D R Photo Management;

p. 269 © Albert Sanchez/CORBIS OUTLINE; p. 271 © Lisa Rose/jpistudios.com.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at

1-866-506-1949 or [email protected]

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at

1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Designed by Dana Sloan

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN 978-1-4391-7778-5

ISBN 978-1-4391-7780-8 (ebook)

To Ellen, for showing me what beauty is

Unbearable Lightness

PROLOGUE

HE DOESN’T WAIT until I’m awake. He comes into my unconscious to find me, to pull me out. He seizes my logical mind and disables it with fear. I awake already panic-stricken, afraid I won’t answer the voice correctly, the loud, clear voice that reverberates in my head like an alarm that can’t be turned off.

What did you eat last night?

Since we first met when I was twelve he’s been with me, at me, barking orders. A drill sergeant of a voice that is pushing me forward, marching ahead, keeping time. When the voice isn’t giving orders, it’s counting. Like a metronome, it is predictable. I can hear the tick of another missed beat and in the silence between beats I anxiously await the next tick; like the constant noise of an intermittently dripping faucet, it keeps counting in the silences when I want to be still. It tells me to never miss a beat. It tells me that I will get fat again if I do.

The voice and the ticks are always very loud in the darkness of the early morning. The silences that I can’t fill with answers are even louder. God, what did I eat? Why can’t I remember?

I breathe deeply in an attempt to calm my heartbeat back to its resting pulse. As I do, my nostrils are filled with stale cigarette smoke that hung around from the night before like a party guest who’d passed out on the living room sofa after everybody else went home. The digital clock reads 4:06, nine minutes before my alarm was set to wake me. I need to use the restroom, but I can’t get out of bed until I can remember what I ate.

My pupils dilate to adjust to the darkness as if searching for an answer in my bedroom. It’s not coming. The fact that it’s not coming makes me afraid. As I search for the answer, I perform my routine check. Breasts, ribs, stomach, hip bones. I grab roughly at these parts of my body to make sure everything is as I left it, a defensive measure, readying myself for the possible attack from my panic-addled brain. At least I slept. The last few nights I’ve been too empty and restless, too flighty—like I need to be weighted to my bed and held down before I can surrender to sleep. I’ve been told that sleep is good for weight loss. It recalibrates your metabolism and shrinks your fat cells. But why it would be better than moving my legs all night as if I were swimming breaststroke I don’t really know. Actually, now that I think about it, it must be bullshit. Swimming like someone is chasing me would have to burn more calories than lying motionless like a fat, lazy person. I wonder how long I’ve been that way. Motionless. I wonder if that will affect my weight loss today.

I feel my heartbeat, one, two, three—it’s quickening. I start breathing deeply to stop from panicking, IN one two, OUT three four . . .

Start counting

60

30

10 =

100

I start over. I need to factor in the calories burned. Yesterday I got out of bed and walked directly to the treadmill and ran at 7.0 for 60 minutes for a total of negative 600 calories. I ate 60 calories of oatmeal with Splenda and butter spray and black coffee with one vanilla-flavored tablet. I didn’t eat anything at all at work. And at lunch I walked on the treadmill in my dressing room for the hour. Shit. I had only walked. The fan I had rigged on the treadmill to blow air directly into my face so my makeup wouldn’t be ruined had broken. That’s not true, actually. Because I’m so lazy and disorganized, I’d allowed the battery to run down so the plastic blades spun at the speed of a seaside Ferris wheel. I need that fan because my makeup artist is holding me on virtual probation at work. While I am able to calm down the flyaway hairs that spring up on my head after a rigorous workout, the mascara residue that deposits under my eyes tells the story of my activities during my lunch break. She had asked me to stop working out at lunch. I like Sarah and I don’t want to make her job more difficult, but quitting my lunchtime workout isn’t an option. So I bought a fan and some rope and put together a rig that, when powered by fully charged batteries, simulates a head-on gale-force wind and keeps me out of trouble.

As I sit up in bed staring into the darkness, my feet making small circles to start my daily calorie burn, I feel depressed and defeated. I know what I ate last night. I know what I did. All of my hard work has been undone. And I’m the one who undid it. I start moving my fingers and thumbs to relieve the anxiety of not beginning my morning workout because I’m stuck here again having to answer the voice in my head.

It’s time to face last night. It was yogurt night, when I get my yogurt ready for the week. It’s a dangerous night because there’s always a chance of disaster when I allow myself to handle a lot of food at one time. But I had no indication that I was going to be in danger. I had eaten my 60-calorie portion of tuna normally, using chopsticks and allowing each bite of canned fish to be only the height and width of the tips of the chopsticks themselves. After dinner, I smoked cigarettes to allow myself the time I needed to digest the tuna properly and to feel the sensation of fullness. I went to the kitchen feeling no anxiety as I took out the tools I needed to perform the weekly operation: the kitchen scale, eight small plastic containers, one blue mixing bowl, Splenda, my measuring spoon, and my fork. I took the plain yogurt out of the fridge and, using the kitchen scale, divided it among the plastic containers adding one half teaspoon of Splenda to each portion. When I was satisfied that each portion weighed exactly two ounces, I then strategically hid the containers in the top section of the freezer behind ice-crusted plastic bags of old frozen vegetables so the yogurt wouldn’t be the first thing I saw when I opened the freezer door.

Nothing abnormal so far.

With that, I went back to the sofa and allowed some time to pass. I knew that the thirty minutes it takes for the yogurt to reach the perfect consistency of a Dairy Queen wasn’t up, and that checking in on it was an abnormality, but that’s exactly what I did. I walked into the kitchen, I opened the freezer, and I looked at it. And I didn’t just look at the portion I was supposed to eat. I looked at all of it.

I slammed the freezer door shut and went back to the living room. I sat on the dark green vinyl sofa facing the kitchen and smoked four cigarettes in a row to try to take away the urge for that icy-cold sweetness, because only when I stopped wanting it would I allow myself to have it. I didn�

�t take my eyes off the freezer the whole time I sat smoking, just in case my mind had tricked me into thinking I was smoking when I was actually at that freezer bingeing. Staring at the door was the only way I could be certain that I wasn’t opening it. By now the thirty minutes had definitely passed and it was time to eat my portion. I knew the best thing for me in that moment would be to abstain altogether, because eating one portion was the equivalent of an alcoholic being challenged to have one drink. But my overriding fear was that the pendulum would swing to the other extreme if I skipped a night. I’ve learned that overindulging the next day to make up for the 100 calories in the “minus” column from the day before is a certainty.

I took out my one allotted portion at 8:05 and mashed it with a fork until it reached the perfect consistency. But instead of sitting on the sofa savoring every taste in my white bowl with green flowers, using the fork to bring it to my mouth, I ate the yogurt from the plastic container over the kitchen sink with a teaspoon. I ate it fast. The deviation from the routine, the substitution of the tools, the speediness with which I ate silenced the drill sergeant and created an opening that invited in the thoughts I’m most afraid of—thoughts created by an evil force disguising itself as logic, poised to manipulate me with common sense. Reward yourself. You ate nothing at lunch. Normal people eat four times this amount and still lose weight. It’s only yogurt. Do it. You deserve it.

Before I knew it, I was on the kitchen floor cradling the plastic Tupperware containing Tuesday’s portion in the palm of my left hand, my right hand thumb and index finger stabbing into the icy crust. I ran my numb, yogurt-covered fingers across my lips and sucked them clean before diving into the container for more. As my fingers traveled back and forth from the container to my mouth, I didn’t have a thought in my head. The repetition of the action lulled the relentless chatter into quiet meditation. I didn’t want this trancelike state to end, and so when the first container was done, I got up off the floor and grabbed Wednesday’s yogurt before my brain could process that it was still only Monday. By the time I came back to my senses, I had eaten six ounces of yogurt.

The alarm on my bedside table starts beeping. It’s 4:15 a.m. It’s time for my morning workout. I have exactly one hour to run and do sit-ups and leg lifts before I get in the car to drive forty-five minutes to the set for my 6:00 a.m. makeup call. I don’t have any dialogue today. I just need to stand around with the supercilious smirk of a slick, high-powered attorney while Ally McBeal runs around me in circles, working herself into a lather of nerves. But even if I’d had actual acting to think about, my only goal today is to be comfortable in my wardrobe. God, I feel like shit. No matter how hard I run this morning, nothing can take away the damage done. As I slip out of bed and do deep lunges across the floor to the bathroom, I promise myself to cut my calorie intake in half to 150 for the day and to take twenty laxatives. That should do something to help. But it’s not the weight gain from the six ounces of yogurt that worries me. It’s the loss of self-control. It’s the fear that maybe I’ve lost it for good. I start sobbing now as I lunge my way across the floor and I wonder how many calories I’m burning by sobbing. Sobbing and lunging—it’s got to be at least 30 calories. It crosses my mind to vocalize my thoughts of self-loathing, because speaking the thoughts that fuel the sobs would have to burn more calories than just thinking the thoughts and so I say, “You’re nothing. You’re average. You’re an ordinary, average, fat piece of shit. You have no self-control. You’re a stupid, fat, disgusting dyke. You ugly, stupid, bitch!” As I reach the bathroom and wipe away the last of my tears, I’m alarmed by the silence; the voice has stopped.

When it’s quiet in my head like this, that’s when the voice doesn’t need to tell me how pathetic I am. I know it in the deepest part of me. When it’s quiet like this, that’s when I truly hate myself.

PART ONE

1

MY HUSBAND left me.

Two months ago, he just left. He had gathered evidence during the trial known as couples’ therapy (it was revealed to me during those sessions that not every woman’s idea of a fun night out was making out with another woman on a dance floor; I was shocked), judged me an unfit partner, and handed down to me the sentence of complete sexual confusion to be served in isolation. I watched breathlessly as he reversed out of our driveway in his old VW van packed with souvenirs of our life together: the van that had taken me camping along the California coastline, that had driven me to Stockton to get my Maltese puppy, Bean, and that had waited patiently for me outside casting offices in LA. As he cranked the gearshift into first and took off sputtering down the street, I ran after him with childlike desperation, panicked that my secret, true nature had driven him away. And with it, the comfort and ease of a normal life.

In a way, I loved him. But I loved the roles that we both played a lot more. I had assigned him the role of my protector. He was the shield that protected me from the harsh film industry and the shield the prevented me from having to face my real desires. Standing by his side in the role of his wife, I could run away from myself. But as his van drove away from our California bungalow with its white picket fence, it became clearer with the increasing distance between me and the back of that van that I was, for the first time in my life, free to explore those real desires. The shield had been ripped from me, and standing in the middle of a suburban street in Santa Monica with new skin and gasping for air, I realized that as his van turned the corner, so would I. It was time to face the fact that I was gay.

I had met my husband Mel on the set of my first American movie, The Woman in the Moon, three years earlier. During the arduous filming schedule of the lackluster indie movie, which had brought me from Australia to the Arizona desert, I entertained myself by creating a contest between him and a girl grip whose name I forget now, mentally listing the pros and cons of each of the two contestants to determine who was going to be my sexual partner. The unwitting contestants both had soft lips and were interesting choices for me. Mel was my onscreen lover and his rival was part of the camera crew that captured our passion on film. Of these two people I had met and made out with, Mel was the winner. The fact that I chose him over the girl grip was surprising to me because, although I didn’t show up to the movie a full-fledged lesbian, I was definitely heading in that direction. During my one year of law school prior to this movie, I’d had an entanglement with a very disturbed but brilliant girl that I guess you could call “romantic” if it hadn’t been so clumsy. By this point, I knew that the thought of being with a woman was exciting and liberating, and the thought of being with a man was depressing and stifling. In my mind, being with a woman was like being with your best friend, forever young, whereas being with a man felt like I would be trapped in adolescence with acne and a bad attitude. So it was surprising to me when I felt a rush of sexual attraction to Mel. (It was surprising to him, too, when I showed my attraction by breaking into his Holiday Inn hotel room, pummeling his chest and face and stomach while yelling “I’m gay,” and then having sex with him.) And not only was I attracted to him, I could actually imagine living with him and his black Lab, Shadow, in LA. The mere thought that maybe I was capable of living a “normal” life with a man made me so excited that at the airport lounge waiting for my connector flight that would take me to Sydney, Australia, via Los Angeles, I drew up another list of pros and cons, this time for getting off the plane in LA.

Pros: 1. Acting. 2. Mel.

Cons:

Almost immediately after arriving in LA, however, the rush of sexual attraction evaporated into the thin air of my wishful thinking. By the end of our first year together, despite my desire to be attracted to him, my latent fear of my real sexuality was simmering and about to boil. I was almost positive I was gay. So I married him. The fact that I got shingles the minute we returned from city hall didn’t deter me from my quest to appear normal, and so my husband and I attempted a happily married life in an apartment complex in Santa Monica that had closely resembled the

television show Melrose Place.

There was a girl who lived next door. She introduced herself to me as Kali, “K-A-L-I but pronounced Collie, like the dog. She was the goddess of the destruction of illusion.” Kali. A quick-witted artist with elegant tattoos and a killer vocab that made you feel like carrying a notepad so you could impress your less cool friends with what you’d learned. Every night she’d be sprawled on the floor of her studio apartment sketching voluptuous figures in charcoal, her thick burgundy hair spilling onto the paper. Every night I’d excuse myself from watching TV with my husband to go outside to smoke. I’d find myself positioning the plastic lawn chair to line up with the one-inch crack where her window treatments didn’t quite stretch all the way to the wooden frame so I could watch her. I would smoke and fantasize about being in there with her, but due to my being married and the fact she was straight and only flirted with me for sport, all we ever had together was a Vita and Virginia–type romance—a conservative exploration of hypothetical love in handwritten notes. She would often draw sketches of me and slide them underneath our door. Kali’s drawings were so precious to me that I locked them away in the heart-shaped box my husband had given me one Valentine’s Day. This was a contentious issue between Mel and me, which culminated in him demanding that I throw them away in the kitchen trash can while he watched. A seemingly endless succession of thick, wet tears dripped into my lap as potato peels slowly covered ink renditions of my face, my arms, my legs.

During my evening ritual of smoking outside and watching her, I was in heaven. Until invariably I was dragged back to earth forty minutes later by a loud, deep voice asking, “Are you smoking another cigarette?” Mel and Kali. Melancholy.

Strangely enough, none of this seemed strange to me. In fact, playing the role of heterosexual while fantasizing about being a homosexual had been my reality since I was a child. At age eight I would invite my school friends over on the weekends and convince them to play a game I called “husband and wife.” It was a simple game that went like this: I, in the role of husband, would come home from a grueling day at the office and my wife would greet me at the door with a martini and slippers. She would cook dinner on the bedside table. I would mime reading the paper. Occasionally, if I had the energy to remove my clothes from the closet, I’d make her remove hers to stand inside the closet’s long-hanging section to take a make-believe shower. The game didn’t have much of a sexual component to it; we were married, so the sex was insinuated. But I carried the role-play right up until the end where I judged my friend on her skills as a wife by timing her as she single-handedly cleaned up the mess we’d made playing the game in my room. Although I was aware of that manipulation (I could never believe they fell for that!), I think my intentions behind the game were quite innocent. I wanted to playact a grown-up relationship just like other kids would playact being a doctor.

Unbearable Lightness

Unbearable Lightness